The geomorphology of the River Taf Estuary as a context for the evolution of the community of Laugharne

Simon Read, Thomas van Veelen

- identify and define the key health and wellbeing values associated with salt marshes including how these have changed over time.

- identify realistic future intervention options for salt marshes, and using the guided outputs of artistic, natural and social science research (including national scale maps), provide evidence-based advice, to a broad range of stakeholders, regarding the management and utilisation of salt marshes to minimise impacts of future coastal flooding events and maximise health and wellbeing

- understand how salt marsh ecosystem components and processes provide health and wellbeing values and to model how different interventions and wider global environmental change, will alter them and, in turn, their value.

- develop and apply novel social science approaches to improve understanding of the health and wellbeing values associated with changes in salt marsh habitats.

Introduction

Any study of the symbiotic relationship between a community and its landscape must be based on an understanding of how each affects the evolution of the other. When research is devoted to a particularly chimerical feature of that landscape such as saltmarsh, it must also require insight into its history and the degree to which it has been a consistently active ingredient in local cultural memory. Landscapes impinge, enable or determine livelihoods to varying degrees: sometimes they dominate, sometimes they are overcome and sometimes they are just accommodated and ignored.

Over the last century, since continuity between the local and global has become increasingly commonplace via information systems and popular media, small local communities need no longer be imprisoned by their own landscape. Due to the development of road and rail communications, coastal communities are increasingly well connected and reliance upon a seaward location for their livelihood has become as much a matter of choice as necessity. Together these ensure that living in a small community is no longer an obligation, an effect of which is a higher level of social mobility. This can be a cause of rupture in the continuity of memory for how communities live with their landscapes, but can promote the development of more generic expectations of the benefits they provide as leisure amenity.

Through this study, I will refer to the writing of Dylan Thomas as a champion for the eccentricity of small isolated communities. In his 1934 BBC radio script “Quite Early One Morning” he developed his idea, “The Town was Mad”, for a town as an asylum, isolated from influences of the outside world. This became the basis for “Under Milk Wood” for which Daniel Jones, in his preface of 1954 comments:

Thomas thought he had found the theme he wanted in the contrast between the mythical town and the surrounding world, the conflict between the eccentrics, strong in their individuality and freedom and the sane ones who sacrifice everything to some notion of conformity

The key focus of this essay is the role that saltmarsh of the Lower Taf Estuary has played in the lives of the community and the extent that it is valued to the present day according to cultural narratives evinced from a range of sources including surviving literary and visual evidence. Although there is an inevitable but not unwelcome risk of straying into other disciplinary territories, an open-ended deductive approach working inwards from a broad overview can lead to surprising congruencies with other methodological approaches and add a dimension to a study that may otherwise not be so readily accessible. For this particular study, we have used available evidence of the topological and cultural conditions that have influenced a societal sense of attachment to or dissociation from the immediate landscape and in particular how this may be applied to such an ephemeral feature as saltmarsh.

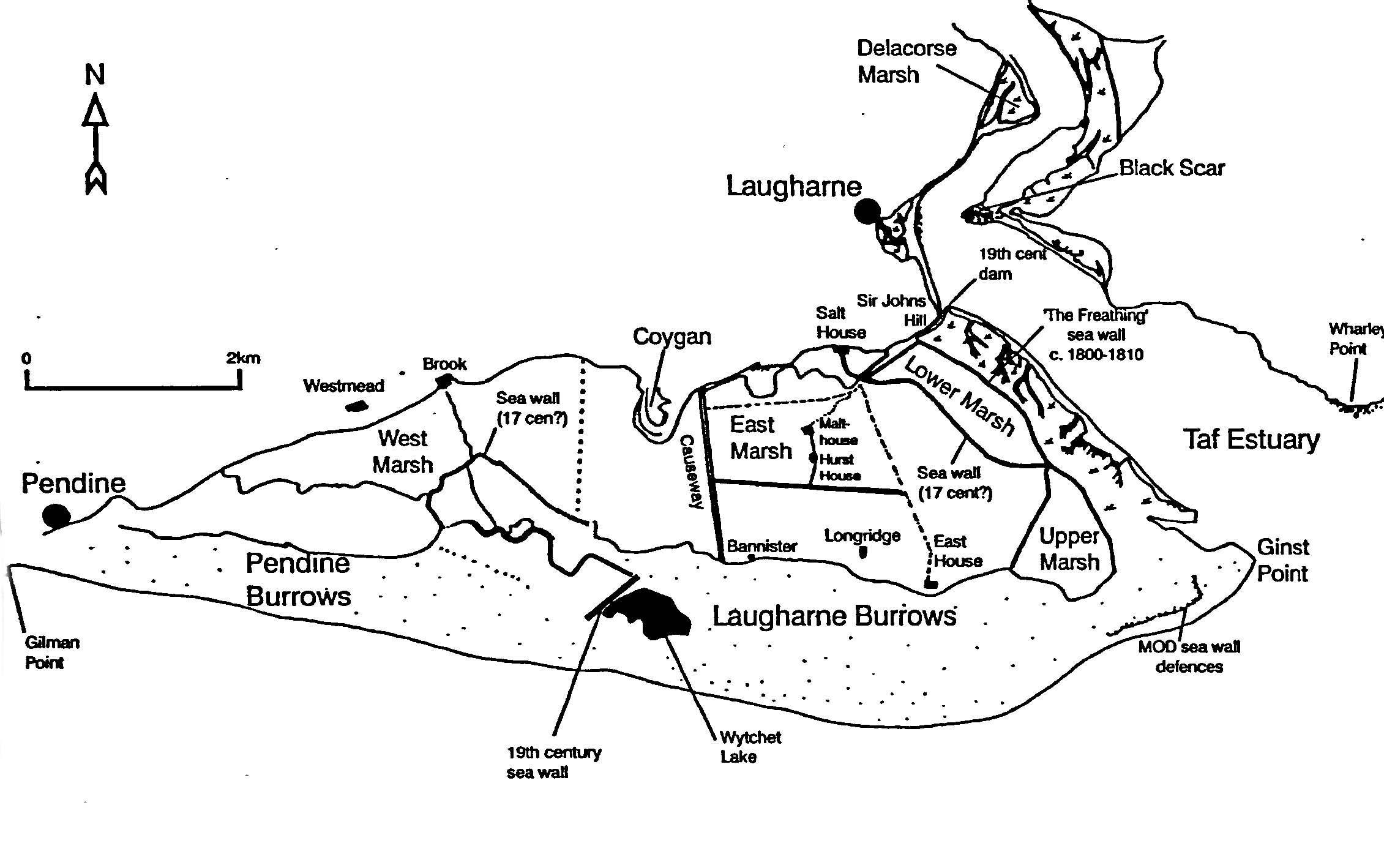

Given the complexity of any dynamic coastal system, speculation upon the society that lives with it must start with a grasp of the evolution of the system itself. What follows is an exploration of the relationship between the community of Laugharne, a small settlement just inside the Taf estuary on the West Coast of Wales and the forcing effect that long-term landscape change has had upon it.

Due to its immediate coastal and estuarine morphology and by dint of its tidal prism, Laugharne became a significant settlement for a certain period of time. But this was not to be forever and, as the Pendine/Laugharne Dune Barrier at the entrance of the estuary pushed ever eastwards, it progressively silted up and the capability to support navigation gradually diminished. Where in previous centuries Laugharne enjoyed strategic prominence as a port with a grand castle to protect it, by 1575 under the stewardship of Sir John Perrot, its role as a stronghold against hostile approach from the sea had become redundant and its status little more than symbolic. In 1664, it finally met its nemesis in the form of Cromwell’s troops, when, this time from a landward direction, it was outflanked, bombarded and breached.

Since my study of Laugharne started as a speculative and eclectic information- gathering exercise, I became increasingly aware that, to ensure credibility, this must to be underpinned by a clear understanding of the geophysical context. The Coastal Scientist, and co-author of this text, Thomas van Veelen kindly introduced me to the work of Stuart Walley on coastal dune barriers and Abdul Kadir bin Ishak upon the sedimentation of the Taf Estuary. Taken in combination, these texts address the dynamic changes the estuary has historically undergone, which the community took advantage of and promoted through reclamation works, until such a time that the continuing process of sedimentation made navigational access to the estuary unreliable and the harbour at Laugharne unviable.

With reference to these two key texts: “The Holocene evolution of a coastal barrier complex, Pendine Sands: Stuart Walley 1996” and “Suspended Sediment Dynamics and Flux in the Macrotidal Taf Estuary, South Wales: Abdul Kadir bin Ishak, 1997”, I have endeavoured to contextualise my enquiry into the morphological transformation of the Taf Estuary driven by the incremental growth and extension of the Pendine/Laugharne Dune Barrier.

Between medieval times and the mid 19th century the Pendine/Laugharne Dune Barrier provided suitable conditions for the development of a viable community, but due to increased siltation and the constraints this has imposed upon easy access to the estuary and the sea beyond, those same sheltered conditions that promoted agriculture, fishery and a thriving township at Laugharne, have eventually led to its separation from an estuary based economy.

In the face of this apparent reversal in fortune, Laugharne remains remarkably resilient and has achieved a renaissance, partly due to the cohesiveness of its community and not the least exemplified by the legacy of Dylan Thomas, whose work, incidentally, is a paean to all that is indefinable in human society. There is a point in its evolution when, any community may have acquired sufficient traction to respond to adversity through adaptation beyond the original conditions of its settlement. As in Dylan Thomas’s Llaregyb there is a strong tendency for a community to develop idiosyncratically in spite of its landscape as much as because of it. Small towns evolve their own genius loci through the individuality of their inhabitants; bloodlines, personal relationship, friendship, neighbourliness and even antipathy forge the peculiar identity of a place that may as much be influenced by its own DNA as by external influences such as loss of livelihood or the injection of a new gentility.

“This is Llaregyb Hill, old as the hills, high, cool, and green, and from this small circle of stones, made not by druids but by Mrs Beynon’s Billy, you can see all the town below you sleeping in the first of the dawn. Less than five hundred souls inhabit the three quaint streets and the few narrow by-lanes and scattered farmsteads that constitutes this small, decaying watering place which may, indeed be called a ‘backwater of life’ without disrespect to its natives who possess, to this day, a salty individuality of their own.”