In this series, my starting point was that the camera should be sensitive to the circumstances of making the picture to the extent that it formed an active and reciprocal relationship with its subject. The upshot of this is that any image produced would have its own a parallel reality.

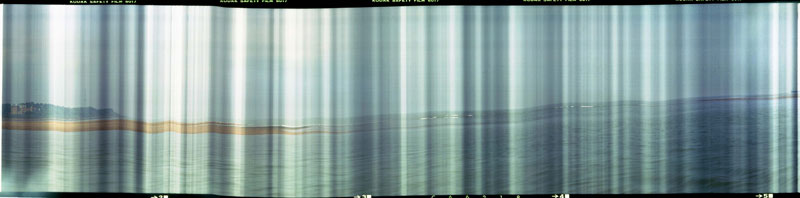

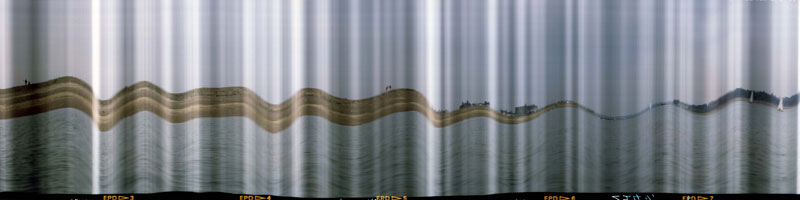

I used a panoramic camera, built by myself to be operated by hand, which goes some way towards clarifying why, given that for the greater part I was working out at sea in a small open boat, they appear to be unevenly exposed. The rhythm of the vertical bars that constitute each picture are a direct transcription of the time it took to make the exposure. This is essentially a scanning process where the exposure is regulated through a fine slit inside the camera as it passes over the film surface, a principle common to all panoramic cameras.

In 1987, as a bid to simplify the arrangements for getting out to sea to make the photographs, I bought a workboat, big enough to be safe but not so big as to be difficult to handle alone. After trial and error I devised a method for taking the photographs that allowed me to stay in control whilst taking each photograph, for which the maximum exposure time would be a minute.

At first I kept the engine running, but the vibration it caused produced a sine wave through the centre of each image, which, although fascinating, was not really the point. From then on, my method was to drive beyond the point that I wished to photograph from, cut the engine, throw out a sea anchor to ensure stability, drift back to where I wanted to be, take the picture and get on my way again as quickly as possible.

Of course this was never going to be simple, but perhaps it goes some way towards explaining why the conditions of taking the pictures became as much the subject of this series as the appearance of the land from the sea.

Art needs reference points which may not even become the main focus of the work: views of land from the sea are a genre, which I use as a point of departure, after all art is not a pre-existing fact, but a parasite that has to start somewhere. Any abstract concern must base itself in concrete reality or else remain conjecture.