Cinderella River

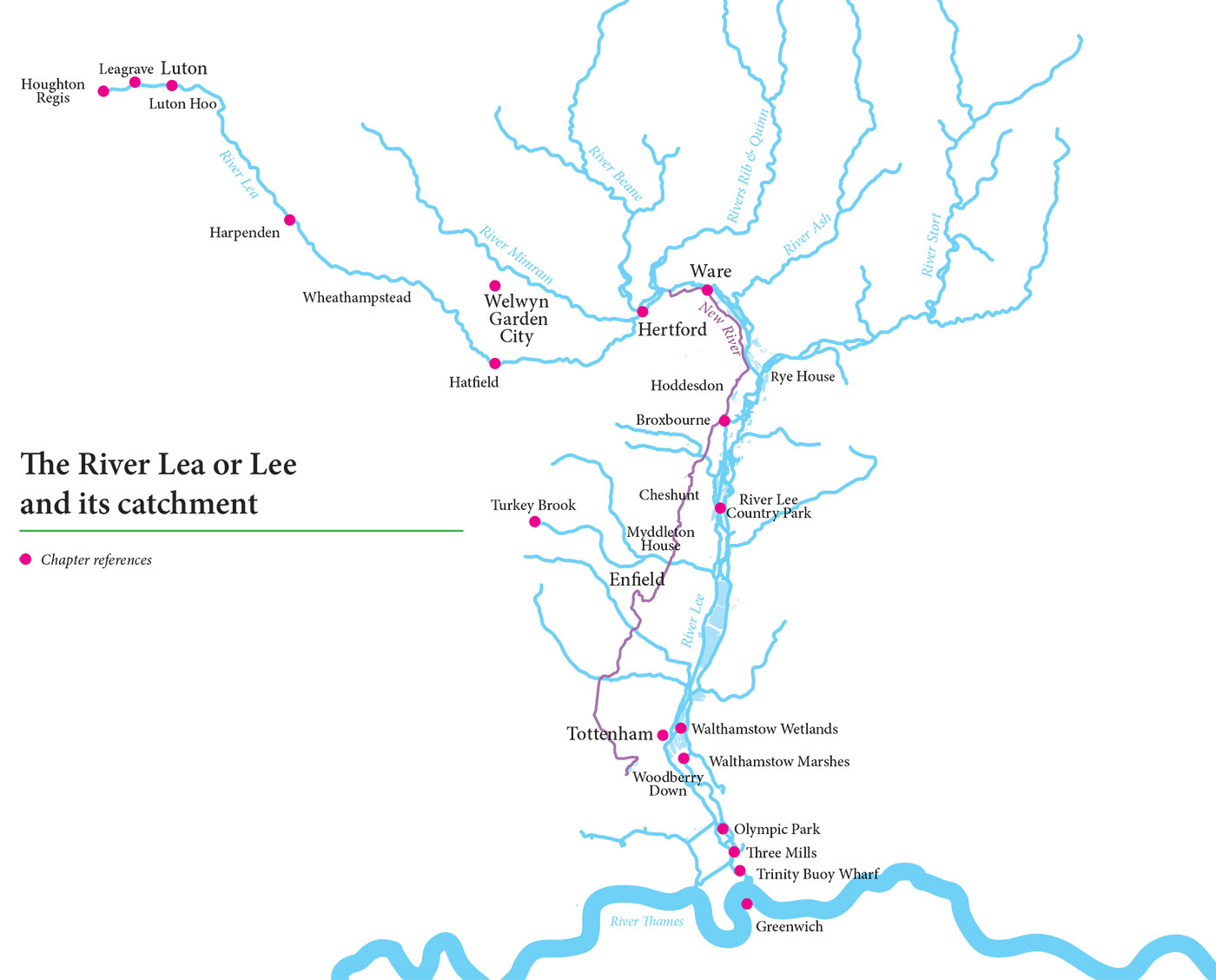

Any river is a compound of its own narratives, and none more so than the River Lee. Unlike the River Thames for which it is one of the major tributaries, the Lee or Lea has consistently eluded stereotype due to the multiplicity of its channel systems and the huge range of functions it has been required to perform between its source and where it debouches at the Thames Estuary.

When is the Lea not the Lea?

Historically spelled as Lea, it remains so from its source to where it is subsumed as the River Lee Navigation at Hertford, beyond which it reverts to its original spelling only where the course of the old river has been retained as an overflow or flood relief channel. Although the long distance path that follows the river from its source through London to the Thames is known as the Lea Valley Walk, the Lee Valley Park Authority, after its inauguration in 1967, gave preference to the spelling more familiar in the lower reaches and in London. But, consistently inconsistent to the end, the site of its confluence with the Thames is Leamouth.

This is a particularly utilitarian watercourse, which as a consequence does not possess sufficient genius loci to divert it from whatever purpose it might be called upon to serve and whichever zone it passes through: for example, it enjoys a little flourish as the picturesque lakes set in the Capability Brown designed parkland of Luton Hoo, after which, with immediate insouciance, it slips downstream and into a waste-water treatment plant on an industrial scale. Along the entire length of the Lee Valley the river weaves itself into a complex labyrinth of flood-mitigation measures, navigable waterways,

freshwater supply, habitat and drain.

My approach to the Hydrocitizenship Lee Valley case study has been to identify what is unique about the River Lee – the common characteristics and the recurrent themes as I follow its curiously fractured journey to London’s River Thames.

What have I discovered? For a great many urban dwellers the Lee Valley is a vital but informal open space. Although historically it has been a Cinderella of a river, both created by and enabling the working industrial landscapes of East London and beyond, now it is undergoing comprehensive transformation into a wetland landscape of such a high level of biodiversity that it has become a model for other major metropolitan environments in the UK and Western Europe. Perhaps this is because it has always been such a busy, marshy and inhospitable place that, since 1965, its post-industrial landscape has by increments been reborn as a luminous green thread that now runs through densely built Stratford, Hackney, Tottenham, Walthamstow and Edmonton

Confluence with the River Beane

out into the open waterlands of the Lee Valley Regional Park. It is bounded to the west by the mainline railway from Liverpool Street Station, further north by the mainline from King’s Cross, and to the east by the Chiltern Hills; and it is fringed by the substantial ribbon developments of Enfield, Waltham Forest, Cheshunt, Broxbourne, Ware and Hertford that just dip their toes in the water. The subsequent explosion of dormitory settlements for London has subsumed the distinctive memories of all of these unglamorous places, finishing where it starts at perhaps the most unglamorous of all, Luton, where, according to the pamphlet published by the Civic Trust in 1964, the river rises unceremoniously in Luton Sewage Works at Leagrave some 90 kilometres north of Leamouth on the Thames. Although the veracity of this claim might be doubtful, it chimes well with the place it holds in the public imagination as the most prosaic and workaday of rivers.

By visiting, talking and walking, I have sought to gain insight into this most complex water environment. I have followed its continual metamorphosis from the growth of industrial East London and the spread of the metropolis over its satellite settlements as continuous conurbation, to the incremental giving back of the wetland environment to nature and for societal well-being in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. It includes the stimulus given to the Lee Valley as a unique environment by the creation of the Lee Valley Regional Park in 1966, the construction of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park for 2012 and the Walthamstow Wetlands initiative, now fully open to the public.

After exploring the variety of locations along the length of the river, I have discovered that certain themes recur predicated upon access, amenity, conserved habitat, water quality and flood-risk management. This text is the first step in an evidential study of the continuous but nuanced interface between people and a water landscape and of how, through partnerships forged at national, regional, local and community level, every effort is made to enable, reconcile and harmonise the conflicting range of demands inflicted upon the river and its environs.

Simon Read

Middlesex University London